A Punk Mind in a Tailored Frame –

POOL dives deeper with Helena Jónsdóttir

21.7.2025

Article by Silja Tuovinen

Images from the archive of Helena Jónsdóttir

***

Where Movement Defies Labels And Frames Become Fluid

“I’ve been doing this for over twenty years, and yet—I still haven’t made my first film… at least not the one with the ideal budget and time.” Icelandic artist Helena Jónsdóttir has been both in front of and behind the camera since she was fifteen. Growing up on an island in the 1980s and ’90s, her primary connection to the worlds of contemporary dance and film came through VHS tapes, television, movies, and the local library.

Helena is a filmmaker shaped by hands-on experience, learning through immersion in every kind of production by observing, and throwing herself into every possible project that came her way, whether it was a commercial, music video, TV show, or film.

Despite the many dance films she has created over the years, she still considers that her “first film” remains to be made.“The field of dance film is just beginning—even if it’s technically a 127-year-old art form.”

She sees a deep parallel between dance and film: both are crafts that cannot be truly mastered in a classroom. They demand hands-on experience, repetition, and a willingness to fail. Helena quotes Samuel Beckett: “Try again. Fail again. Fail better. And then, try again.“

Helena adds her own advice:“It is through doing that you get to know the equipment, understand movement, and—over time—begin to hear how they speak to you. That’s when your artistic voice begins to form. It’s a love relationship—one that demands both time and patience.”

“Right now, I see us dancing between music videos, visual art, and filmmaking. In a way, it’s like having a punk mind in a tailored frame.”

It is precisely in the unfinished, evolving nature of the field that Helena finds the greatest excitement and hope for the future of dance film.“We are allowed to create film art outside of the so-called ‘rules and structure’—it’s still very much in the making. It’s like we’re finding new voices, experimenting with approaches that offer freedom. This is at the core of being a dancer. You learn all the techniques and styles, and once you’ve mastered them, you throw them away to create your own unique style.”

At present, dance film wears many names and navigates between dance, theater, film, musicals, music videos, documentaries, and visual art. Helena believes this fluidity exists because the form doesn’t yet belong to any one category—it’s still finding its identity. “Right now, I see us dancing between music videos, visual art, and filmmaking. In a way, it’s like having a punk mind in a tailored frame.”

Teaching Dance Film: Play, Explore, Create

Helena’s journey into teaching dance film came unexpectedly, but it has become a vital part of her work. Her fundamental approach is simple: use games and play to unlock creativity. “I encourage students to experiment with ideas and the camera, to fail, and then try again—over and over. Games are fantastic tools for finding your artistic voice.”

Her process begins by meeting students where they are. “The first step is to understand where each group is at, then introduce tools that fit their needs. We explore what’s already been done in the field—and then, we throw it all away to start fresh.”

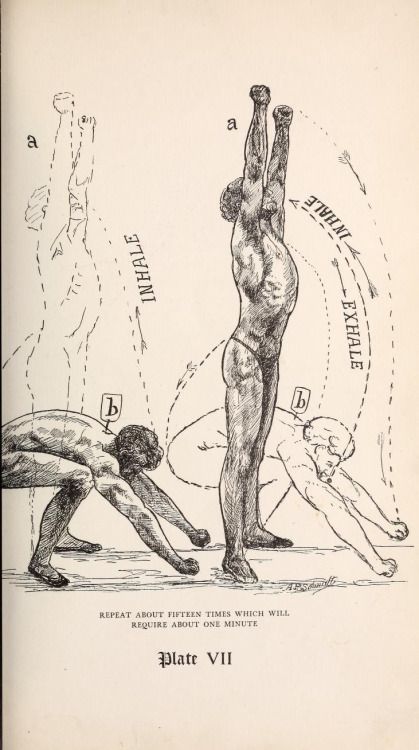

From there, the class moves from ideas to moods, storyboards, and tentative scripts, all through playful experimentation. “We use exercises to discover strengths and weaknesses, and to practice developing an artistic voice. Creativity becomes our game plan for exploring where the work can take us.” A core focus is exploring the language of the body. “What is it saying? What types of movement fit a scene? Can we expand the vocabulary of how to capture the moving body on camera? Is the camera a dance partner, or another dancer?”

“That’s why dancers are fantastic filmmakers—it’s already in them.”

Helena blends traditional film techniques—close-ups, two-shots, long shots—with choreographic concepts, inventing new “shots” like the “pirouette shot” or “chassé shot . “Why not? Any help to tell stories from a dancer’s perspective. “It’s about translating the movement of the body into the movement of film. Dance training emphasizes continuity—how one movement flows into the next—and Helena believes this naturally prepares dancers to be exceptional filmmakers. “The only trick is having time to explore how filmmaking tools can capture story through movement. That’s why dancers are fantastic filmmakers—it’s already in them.”

From the Dance Studio to Camera Lens

Most dancers are trained in studios with the stage as their primary focus. For Helena, the challenge of dance filmmaking lies in adapting this stage-based knowledge for the screen.“All of a sudden, you’re breaking down the walls—asking, how can we move through the screen?,” she explains. “In a live performance, the audience acts like the camera; they choose where to look and experience the moment in real time. But in film, the director must decide exactly where the viewer’s focus lies.”

Helena cites Merce Cunningham’s insight: “On stage, movements need to be enlarged for the audience, but for the camera, it’s all about the details.” This means translating dance language into the language of the camera. Helena points to DV8’s Enter Achilles as a prime example of successfully moving dance from the black box stage into a real-world location—a bar—showing how film can open new dimensions for choreography.

From Mini-DV to Mastery: Helena’s Journey With the Camera

Helena’s first camera was a Mini-DV Sony handed to her by her late husband. “I grabbed the camera and just started playing with it—I fell in love immediately. It felt so natural. I’d never held a camera myself before, but I knew the basics from years of working both in front of and behind the camera for others.”

Her first instinct was to see the camera as her dance partner. “From there, I began exploring space, light, movement, and editing. My earliest films were shot on Mini DV tape. Coming from live performance, I often filmed in one continuous take, using the camera’s pause button instead of heavy editing. It was a fantastic exercise.”

Drawing from her analogue filmmaking past, Helena’s favorite creative tool remains the budget—specifically, working with very limited resources. “If you only have 50 euros, you have to be incredibly creative in finding locations, performers, and everything else. That’s why many of us dance in our own films, myself included. It’s stressful, but it pushes your creativity and teaches you so much. It prepares you to be a director.”

I haven’t made my ‘first film’ yet—the one with the ideal budget, dream team, and time. I always say if you could give an artist time and financial security, they would create amazing things.

Later, Helena was fortunate enough to work with budgets in the thousands, but she credits her early experiences with low budgets for enabling her to maximize those resources. Yet, she acknowledges that the lack of funding for dance film remains a major hurdle for many artists. “I haven’t made my ‘first film’ yet—the one with the ideal budget, dream team, and time. I always say if you could give an artist time and financial security, they would create amazing things. Right now, if I’m lucky, I make a film every other year.”

It’s widely known in the film industry that making a film can take up to ten years—and there’s good reason for that. However, Helena encourages emerging filmmakers not to let limited resources hold them back. Embodying a genuine Icelandic spirit, she urges artists to take action and get involved rather than staying isolated, wondering how the industry works.“My advice is simple: do what you do in dance—take classes. In film, that means going on set, working with someone who is doing something, anything. That’s where your journey begins.”

Connecting Through Physical Cinema

Through her films, Helena discovered a desire to reach audiences beyond the traditional dance and art worlds. “I wanted to connect to my mother, my family, everyday people who usually don’t go to see dance or art outside of television,” she explains.

This motivation led her to develop a cinema-choreographic language she calls physical cinema. “I use physical movement as a language—an extended form of body language. I work with actors, dancers, and increasingly with non-dancers—natural movers. I explore body language and write new narrative choreographic scripts, aiming to create a language that a broader audience can understand.”

Helena believes that everyone is a dancer, but somewhere along the way, many of us lost the “license”to dance. “In the Western world, public spaces for dancing have diminished. Outside the home, you often have to join a dance class or go to a bar with flashing lights just to move freely. But movement is so important, and more people are recognizing that now.”

Dance reconnects us with our bodies and ourselves

Dance, one of humanity’s oldest art forms, offers empowerment as well as physical and mental health benefits. Yet, in modern life, we spend increasing amounts of time sitting still. “Dance reconnects us with our bodies and ourselves,” Helena says. “It reminds us how essential movement is to our well-being.”

Reclaiming Movement As Language

When Helena first began working in film, she quickly realized that audiences outside the contemporary art world often didn’t understand the language of dance. For many, the word “dance” still evokes familiar images: musicals, ballet, ballroom, pole dancing, or maybe street dance—styles that are highly technical and often reserved for performance, not for spontaneous everyday expression.“Most people don’t think of dance as something they can do,” Helena says. “Unless it’s in a class or on a stage, they feel it’s not for them. But I believe we are all writers, singers, dancers—and we should do it much more.”

Helena cites Sir Ken Robinson’s famous TED Talk Do Schools Kill Creativity?, where he discusses how young children are naturally expressive, but gradually lose that freedom. “So many parents have told me their four-year-old is a contemporary dancer—and somehow, we grow out of it.”

Dance is expression. In my films, it replaces spoken words—it becomes the conversation

In Helena’s dance filmmaking, movement is the dialogue. It’s a language. “Dance is expression. In my films, it replaces spoken words—it becomes the conversation.” Currently, Helena is developing a choreographic scriptwriting method in which each movement or gesture is written as a form of dialogue. For instance, placing a hand on someone’s shoulder might equal “hello.” She explains:“I’m writing down both the movement and the motivation behind it—why the dancer moves that way in the context of the scene.”

This approach emerged from a practical need: applying for traditional film funding. Without conventional dialogue between characters, dance films are often difficult for selection committees to interpret. “Since we don’t write spoken scripts, we have to find new ways to communicate our stories clearly, especially for funding applications.”

Helena is excited about the potential of this method—not only to support production, but also to inspire collaboration. “I’m looking forward to sharing this with my colleagues and exploring it even further.”

Fascination with The Everyday

It’s easy to assume that anyone with access to Iceland’s dramatic landscapes would automatically use them as a cinematic backdrop. But Helena Jonsdottir takes a different approach. Instead of vast glaciers or waterfalls, she chooses to film in apartments, houses, and other indoor spaces. “I’m lazy in a way,” she admits with a smile, “I like having a toilet and a kitchen nearby when I’m filming. I’m drawn to stories that naturally take place in those environments—homes, apartments, and familiar indoor spaces.”

Her preference is not only practical but deeply connected to her artistic vision. “After working on commercials shot on glaciers or in front of waterfalls, I realized how many variables there are—the unpredictable Icelandic weather, airplanes, tourists, traffic, and often freezing cold. It made me realize that I’m more interested in the quieter, everyday stories. And those are often best told indoors.” To Helena, domestic spaces are rich with emotion and narrative. “Apartments immediately carry the lives and stories of the people who inhabit them. The way a space is used—the way someone moves through a hallway or sits in a kitchen—adds so much to their story.”

Though she often works with a static tripod, she sees potential for the camera itself to become a creative partner. “I’m still working on finding my own direction, even though the camera hasn’t moved much yet,” she says. “I hope to explore it more deeply—as a kind of dance partner—when time and budget allow. For now, I remain focused on what moves the person and the story.”

I love watching people, especially when they’re waiting

The everyday has always fascinated her: daily routines, subtle behaviors, mental health, and the quiet richness of creativity. “I love watching people, especially when they’re waiting—back before phones took over those moments. There’s something beautiful in waiting—those unaware, vulnerable pauses. I’m fascinated by how people stand, sit, walk, and run—how different we all do it.”

Through the medium of dance film, Helena seeks to translate these observations into movement—whether through the body, sound, or camera. “I try to use movement as a language to tell the story. To help people connect—to themselves, and to each other. And maybe, just maybe, to feel good about themselves.”

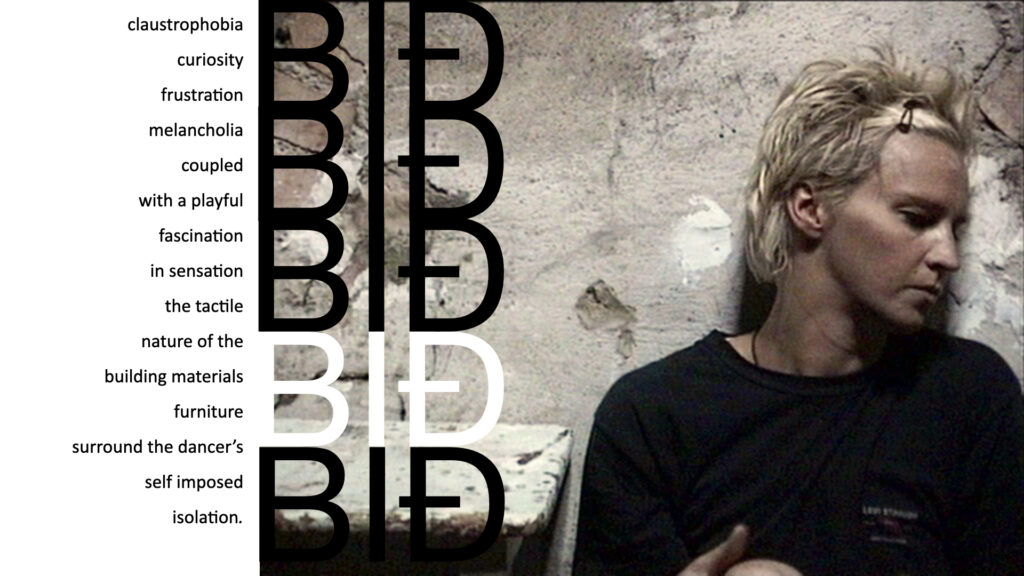

Birgir

One of Helena’s most widely screened films is Birgir, a deeply personal work created in collaboration with her electrician. “As a young boy, Birgir struggled with his weight and was bullied at school. His home life was difficult, leading him to be raised by his grandmother. He grew up feeling isolated and lost. Over the years, he tried everything—diets, doctors, exercise—but nothing seemed to work. Then he discovered “free dance,” and everything changed. He finally arrived in himself. Dance saved his life. Today, he is a thriving, strong, and positive person.“

The idea for the film was born while Helena was working on a dance project at her living room table, and Birgir was fixing her electricity. They struck up a conversation. “He asked me what I was working on,” Helena recalls, “and when I told him, his eyes lit up. He got very excited and immediately asked if he could show me his discovery of dance. I was honored. We agreed to meet later that week. I told him to choose his own outfit and a location that felt right to him—and I would simply be there to capture it.”

Birgir chose a black sand beach in Reykjavík and wore a striking green shirt. And then—he just danced.“It was the most beautiful dance I’ve ever seen,” Helena says. “Dance isn’t about how high you can lift your leg or showing off your flexibility. It’s about being present. It’s a bout loving the moment, and letting it move through you.” The encounter with the electrician captures Helena’s approach: revealing the beauty within and inspiring others to move, create, and connect.

“Now more than ever, we need creativity and the arts to help us navigate isolation, loneliness, and even depression—through this unsettling time we’ve brought upon ourselves.”

HELENA JÓNSDÓTTIR

Helena Jonsdottir is an acclaimed and award-winning multidisciplinary Icelandic artist whose practice spans choreography, dance, filmmaking, and visual art. With a career of over three decades, she is known for her unique exploration of everyday movements—both of the body and the mind—while deeply engaging with the present moment and the influence of surroundings. Her work is grounded in the concept of “movement” and is expressed through physical theatre, film art, video installations, and acrylic and ink painting.

Helena has received numerous awards and recognitions for her innovative and thought-provoking work, which has been featured internationally in festivals, galleries, museums, on television, and on stage. She is particularly celebrated for her ability to blend artistic forms, creating immersive experiences that transform the familiar into something unexpected and emotionally resonant.

She received her training at the National Theatre Ballet School of Iceland, continued her dance studies at the Alvin Ailey School in New York, and pursued film studies in Los Angeles. Helena is widely respected as a pioneering artist who works with open-source mediums and collaborative practices, continuously pushing the boundaries of contemporary performance and visual expression.